The Music Motif Baked into Percival Everett's Award-Winning James

Like a lot of Percival Everett's work, music references are a main ingredient of James.

CONTAINS SPOILERS FOR JAMES

James by Percival Everett is good—like, well-made-croissant good. It’s intricate, flaky, and buttery inside, a book so full of layers it is hard to keep track of them all.

My favorite layer, by far, is a rarely mentioned music motif. I tracked this layer carefully.

Music, as an ingredient in James, speaks to the era’s Mississippi riverboat music traditions, the Black roots of Americana music, and the author’s own identity as a contemporary “blues and old-timey country” musician.1

Below, I outline the 9 aspects of James’ music motif. This information comes from my careful music annotations, something I annotate in every book I read.

At the end, please tell me what you think.

Did you notice this motif? Did it work for you?

Did I miss anything? What would you add to my observations?

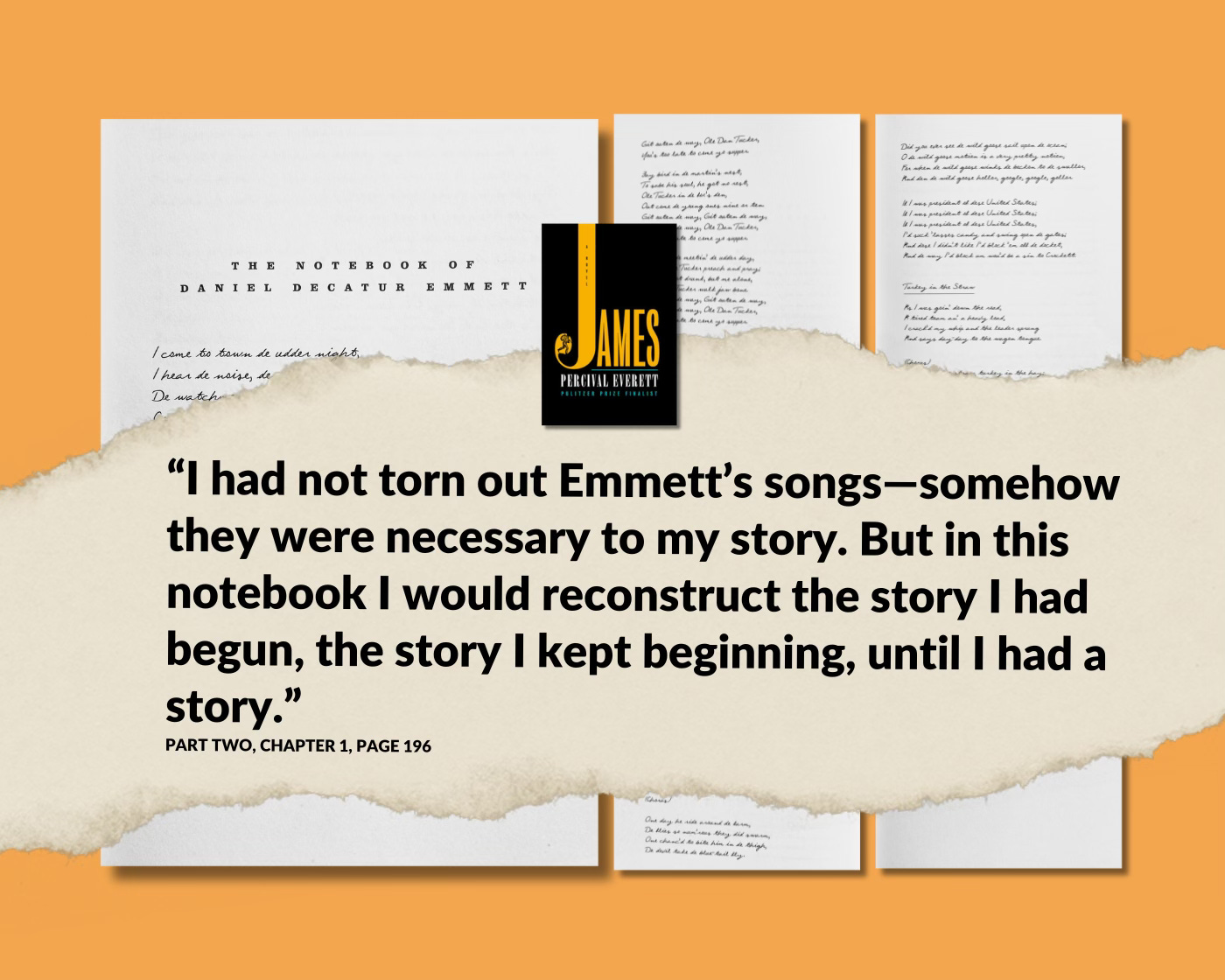

1. Daniel Decatur Emmett’s Notebook

James’ multidimensional music motif starts on page one. The first words of James, which are (surprisingly) not written by James, belong to the wretched songwriter Daniel Decatur Emmett. (This is the guy who popularized blackface minstrel performances and wrote “Dixie.”)

For 184 pages, it’s a bit of a mystery why the beginning is setup like this. In due time, we get the reveal: James takes “Emmett’s leather notebook, the one with his songs” at the very end of Part One.2 Then, on the remaining pages, he writes down his own story, but not without this consideration:

“I thought about tearing out his songs and burning them, but they would still exist. […] Better to know they exist. Don’t you think?”

Part Two, Chapter 3, page 202

The Daniel-Decatur-Emmet-notebook beginning is serious (and humorous). To lay it out: Everett, a Black novelist, painter, musician, and poet, creates an enslaved Black character who is a writer. What a powerful concentration of Black creative energy, right? That’s the point. The energy is a direct lightening strike on a white songwriter—known for blackface—and it vaporizes him off his own pages. This notebook and creative space, no longer Emmett’s, becomes the site of James authentic testimony. Touché. 3

2. A musician gives the pencil to James, as well as the best storytelling advice.

Young George, a banjoist and luthier, acquires the pencil that James uses to write this book.4 About his instrument he says:

“I made it,” Young George said. “But I dare not play it here. Ain’t nobody around, but sound travels, you know? Especially, music…”

Part One, Chapter 14, p 86

When Young George gives James the pencil, he offers storytelling advice only a musician could give. Invoking playing by ear, he says:

“Use your ears […] Tell the story with your ears. Listen.”

Part One, Chapter 15, p 91

3. James often has musicality on his mind.

The book’s first musical moment comes quickly, right after James’ opening lines.

First Sentence:

“Those little bastards were hiding there in the tall grass.

Top of Next Page:

🎶 “Those boys couldn't sneak up on a blind and deaf man if a band was playing.

From this start, we get a sense of how often James will think of music in the book (a lot). James consistently proves to us, with his music observations, that he has an ear for natural and manmade rhythms.

Examples:

“the music, laughter and sloshing of the big wheel from the riverboat” (p 76),

his own slowing heart beat (p 97),

the drumbeat of a Ferrier pounding steal (p 153-154),

the meaning of birdsong while running (p 218),

the music of the Mississippi River’s “rhythmic churning (p 220),

“The sounds of the river sloshing and the paddle churning made scary music.” (p 231)

the hypnotic beat of Brock’s steady coal tossing (p 240).

Lastly, on this topic, when James bears witnesses to violence (the lynching of Young George 💔 and the rape of Katie 💔), his language in these moments is musical too. He writes down the haunting soundtrack of these events, which consists of the same three sounds: “slap,” “sick,” and “bad.”

“A slap […] sick thuds full of bad rhythm and punctuation."5

“The slapping […] was […] sickening […] bad music for any ear at any time.”6

4. A bold, fun musical anachronism.

Like Twain in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Everett works some anachronistic details into James.7 James tells Sammy on page 220 that the Mississippi River is “Too thick to navigate and too thin to plow. I heard someone say that once.”

That someone is presumably Mark Twain8, and that line gets incorporated into a song on John Hartford’s 1976 bluegrass album Mark Twang. The song is “Let Him Go on Mama.”

I don’t think there is a deep read of this anachronism. Like many anachronisms, I think this is the simple case of an author having fun with a piece of art he loves and working it into his book. There’s precedence for this in Everett’s other works: "Ain't No More Cane / I Will Rise Up" by Lyle Lovett was Everett’s seed of inspiration for The Trees. In The Trees, you can hear a few lyrics from the song directly quoted. The choral sounds of the song have a major influence on the ending of the book, too.

5. The Bard Himself is a “Songwriter” in James

When the Duke and the King enter the story, James writes down the string of references they make to “that English fellers Shakespeare […] that songwriter from the old country what writes poems, plays, and such like.”9

Fun to note: The Shakespeare references in James differ a little from the ones in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Everett’s reworked choices are funny!

6. When James sings with The Virginia Minstrels

James, a talented tenor, gets “discovered” by Daniel Decatur Emmett while he is singing a work song with Easter. Emmett purchases James to replace the troupe’s tenor who absconded. James joins up with no choice, but eventually escapes with another Black performer, the drummer Norman. This all happens in Part One, Chapter 28-32.

Not going to go over this whole episode here in any more detail. It deserves its own separate deep dive one day.

7. Teaching Huck to hear the voices of the rivers

At the end of Chapter 12 in Part One, James breaks a long, difficult silence with Huck by asking if he can hear the voices of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. The short scene is beautiful and bluesy. James daydreams about freedom for his wife Sadie and Huck’s half sister Lizzie.

Huck closed his eyes and listened. "I don't hear it."

"It's the Ohio, Huck. She be tellin' dat ol' Mississip 'bout freedom. I'm gonna get me a job and save me sum money and come back and buy my Sadie and Lizzie."

Part One, Chapter 12, page 78

8. Hopkins is singing just before James silences him forever.

Hopkins uses his body as an instrument of violence. When James stops him from ever raping or committing crimes again, he also stops the man’s drunk, celebratory song.

“My anger found full flower as I approached him. He was half sleeping, still drunk-humming his song.”

Part Three, Chapter 7, p 281

9. Everett’s lyrical couplets and near rhymes.

Everett is a poet, and you can hear music, or poetics, in a lot of Everett’s prose. Here’s some of the rhyming, rhythmic moments in James that I annotated as I read:

Part One, Chapter 18, p 105

“I was the horse that I was, just an animal, just property, nothing but a thing, but apparently I was a horse, a thing, that could sing.”

Part One, Chapter 30, p 170

“Then I understood it really didn’t matter. We marched in step, then fell into a cakewalk stagger.”

Part X, Chapter 9, p 287

“The planks of the floor spoke, but sounded enough like the settling of the house that no one would take note.”

Part Three, Chapter 11, p 302

“All of those with me stopped and watched the man receive the lead. His chest exploded red […] He did not fall like a tree. [..] Her merely fell […] into a darkness none of us could see.”

That’s it. Let’s talk about James; let’s talk about music; let’s talk about great writing in the comments.

https://lithub.com/its-harder-for-me-to-talk-about-them-percival-everett-on-the-paintings-he-makes/

Part One, Chapter 32, page 184

whole post about this first line:

Part One, Chapter 16, p 96

Part Three, Chapter 6, p 278

I googled, but I couldn’t determine if Mark Twain said it first definitively.

Part One, Chapter 20, p 120